Inferring Ingredients from Food Images

Knowing what we eat is cool nowadays. People can’t stop taking photos about their meals and uploading them everywhere. Sometime soon a cool App with ingredients recognition and nutritional info inferring will come out and get trendy, at least for a while.

Taking profit of the joint images-text embedding explained here I have built a pipeline that recognizes ingredients in cooked food images. Both visible and non visible ingredients (statistics involved here). I did this experiment 2 weeks ago because a collage built a dataset of images tagged with the ingredients. He had trained a multi-label classification CNN on that, and I wanted to check if this pipeline outperformed it. And it did.

The dataset

I cannot share the dataset because it’s not mine and it’s not public yet. But I’ll link it here as soon as it is.

The dataset is formed by //images with their associated ingredient list//. They have been compiled from Yummly, a cooking recipes website (it can easily be done with their API). It’s a //small dataset: We have 101 different types of food dishes and 50 images of each one//. The ingredients have been simplified (so white wine → wine). After that simplification we end up with 1014 different ingredients.

The pipeline

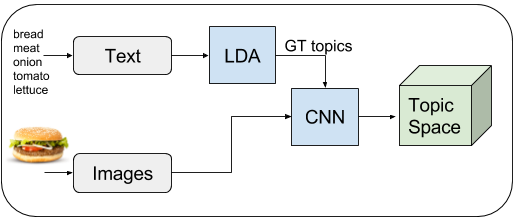

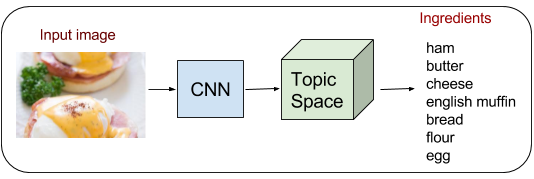

The pipeline is similar to the one explained in this post, so read it for a detailed explanation of the text-images joint embedding (LDA training, CNNtraining…). We train an LDA using the ingredients associated to images. Then we train a regression CNN to regress topic probabilities from images. To infer ingredients from images, we regress topics using the CNN and then we go from topics to ingredients.

The python code to train the LDA, the topic regression GoogleNet and build the whole ingredient inferring pipeline is available here.

Training

First of all we train an LDA using the ingredients associated to the images. We tried different number of topics, but the top performing dimensionality was 200. Once the model is trained, we infer topic distributions from the ingredients list associated to each image. Then we train a Googlenet CNN to regress topic distributions from images, using as groundtruth the topic distribution given by the LDA for the image associated text.

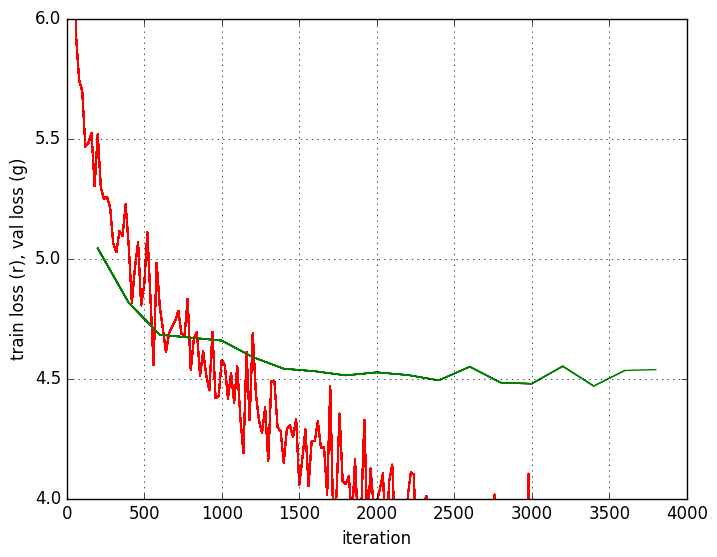

As it can be seen in the figure, in this case the training was fast. With just 2000 iterations (batch size 100), the model has already learned and overfits. That’s because the dataset is very small. 2000 iterations with batch size 100 are 40 epochs.

The training parameters for both the LDA and the CNN training were the same as in here.

Testing

In the testing phase we first infer with the CNN a topic distribution from the image. To infer the ingredients from the topic distributionwe set two thresholds:

- Topic score threshold: Only topics with a score higher than this threshold can contribute with an ingredient.

- Ingredient threshold: Only ingredients with a score higher than this threshold are accepted.

The topic score is the value regressed by the CNN for that topic. The ingredient score is the value regressed by the CNN for a topic multiplied by the score of the ingredient in that topic.

Results

Analytic results

Those are the Precision, Recall and F-Score results of the baseline, which was a Googlenet trained for multi-label classification of the 1014 ingredients, the explained pipeline using an LDA with 200 topics and an LDA of 500 topics.

Qualitative results

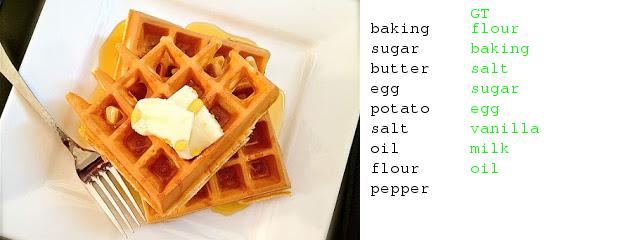

Inferred ingredients by the LDA 200 pipeline in black, groundtruth ingredients in green.

Conclusions

Though the shown results seem great, this dataset is too small to learn ingredients representations. The main problem is that we have only 101 different food dishes. So a CNN learns to recognize the dish, and then statistically infers the ingredients. It’s not really recognizing ingredients. Also, we should have different food dishes in the train and the test set, so we cannot prove that the net can extrapolate the ingredients recognition to other dishes.

After this experiments and conclusion, we decided to expand the dataset, given that the pipeline seemed to be working but we needed more data to prove it with certainty. So we expanded the dataset to 200 different food dishes and 100 images of each one, and building a test set of unseen dishes. But when we were going to start the experiments with the expanded dataset a CVPR2017 paper from the MIT came out (and it’s already in the media). They were working in the same task, but had a much larger dataset, a much larger and good looking pipeline and a lot of work and money behind. So I stopped working in ingredients recognition. Retreat on time is a victory